Strip Search

Entertainment Weekly

By Troy Patterson

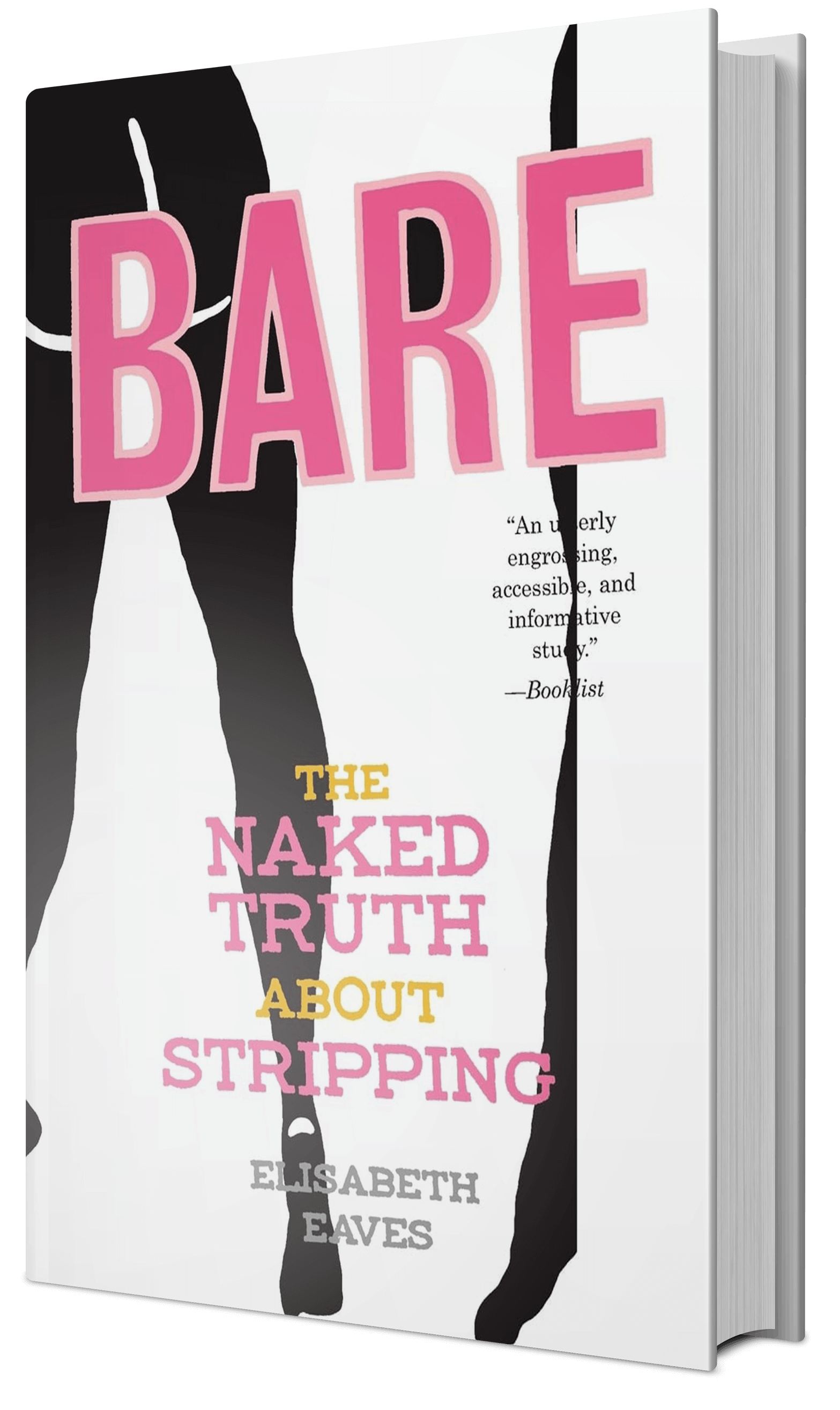

In her book Bare, former nudie-club dancer Elisabeth Eaves gets beneath the profession’s skin-deep image.

It is natural that a single 31-year-old woman would be nervous to descend into the neon-accented murk of Flashdancers, a strip joint just north of Times Square, but in Elisabeth Eaves’ case, the timidity owes not to modesty. Her first book, Bare: On Women, Dancing, Sex, and Power (Knopf), a melange of memoir and analysis, was sparked by her ambivalence about having once earned a living by slithering around a peep-show stage in black knee-high stockings and matching heels. Ah, but once she catches a whiff of the place, she floats in on a cloud of nostalgia. “All strip clubs must use the same cleaning products,” she says. “It could be baby wipes, Windex, whatever they use to clean the poles.”

It’s a slow Wednesday afternoon. Three fake blondes wearing pouts, thongs, and platform heels shiftlessly swing their hips to generic thumping techno-pop. In back, two colleagues attentively grind against a pair of patrons in sober suits. Sipping a $ 9 Coke, Eaves is engaged but unimpressed: “I have the utmost respect for good erotic dancing, but I’m not seeing any of that. Those two girls are just standing there chatting.”

Like Lily Burana’s 2001 Strip City–which Eaves, fearing influence, has not read–Bare details the ecdysiast’s job duties. It also considers issues from sexual politics to the niceties of selecting a stage name. “Strip clubs,” she writes, “were full of double-L names. Lilies, Lulus, Lolas The two Ls made the person saying the name flick the tongue up and down in a licking motion.” She was Leila.

An academic’s daughter who grew up in Vancouver–a town distinguished by its “high-end stripping scene”–Eaves first visited nudie bars as a teen (“better than going to a movie on Saturday night”). As a dancer at Seattle’s Lusty Lady, she took to the instant cash, flexible scheduling, and constant ego gratification (“the power trip feeling of like, you know, I’m showing off and you’re giving me money”). Four years ago, while an international-affairs grad student at Columbia, she realized there was “something unresolved” to figure out: “There’s an idea widely across society that women are for sale, and I contributed to that. That’s the conflict.”

The question “Is this a feminist book?” earns a six-second pause. Then Eaves gives a hesitant yes: “It’s about women making their own choices and dealing with the consequences. It’s honest about sexuality, and I think sexual freedom is just as important as any other right, and it’s been a long time coming for women, even after a couple waves of feminism. So, I hope so.”

She excuses herself to the ladies’ room and returns to report it’s in the dressing room, which contains the usual stuff. “Makeup bags, costume racks, bags of chips, curling irons and blow-dryers A woman just asked me how the weather was. I’ve had that experience too. These places never have windows.”