What is Lab Lit? My First Speaking Gig of the Year

Issue #10

January 28, 2024

Around five years ago, I had the idea to write a novel that explored the dark side of a scientific breakthrough. I’d been working at the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, where the beat was basically technology that could kill everyone really quickly, from nuclear and biological weapons to fossil fuels to artificial intelligence.

Into this theme I brought a story about a young neuroscientist and biotech exec, who also happens to be a reformed psychopath looking for someone from her past. The novel is called The Outlier, and will be published by Random House Canada on August 6th.

Now, on February 9th, I’ll be part of a live panel on science in fiction at the AWP annual writer’s conference in Kansas City. Yes, that’s science in fiction – literature that explores the real-world science of yesterday and today, rather than future possibilities. Some call it Lab Lit.

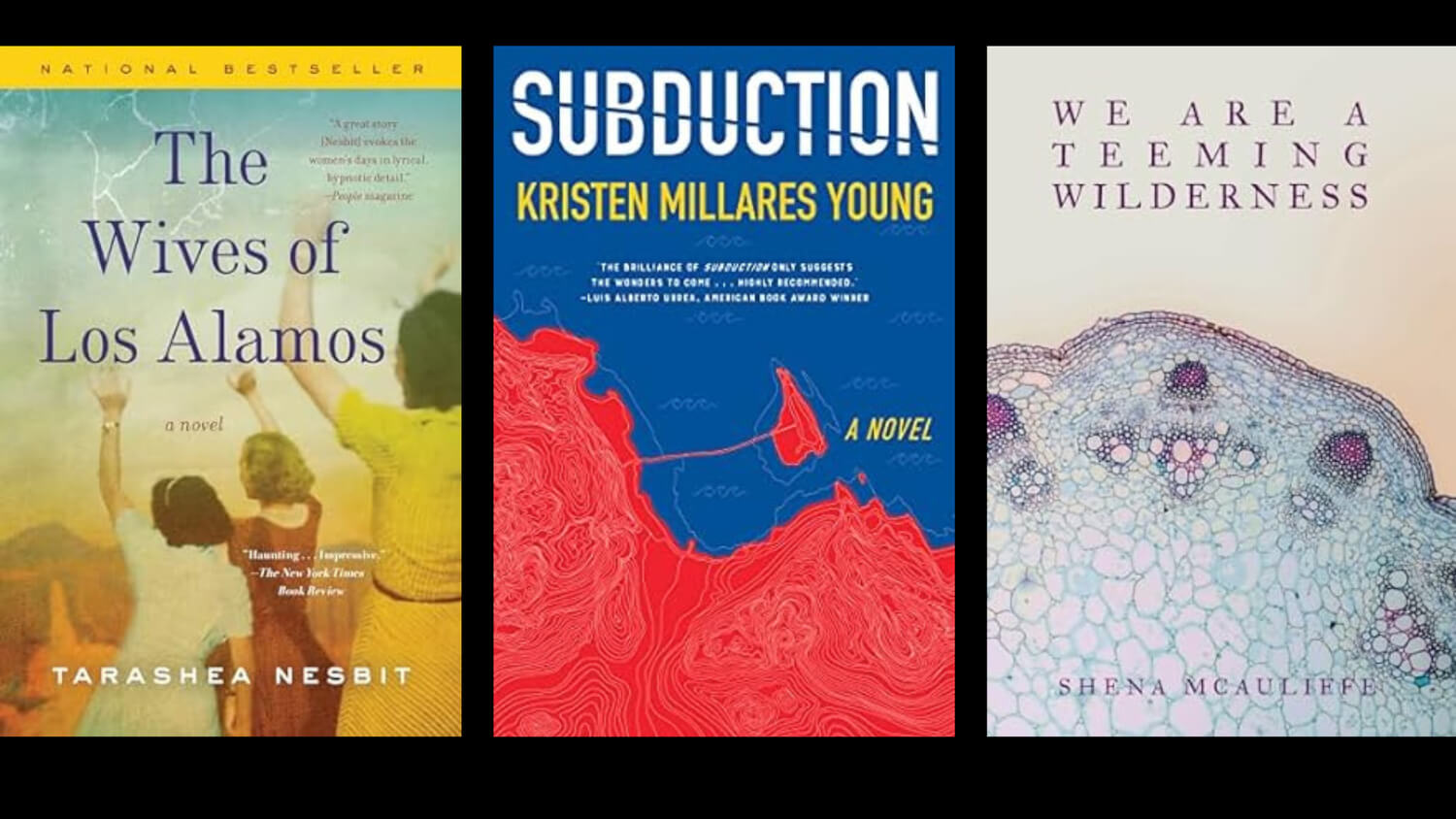

Joining me on the panel will be TaraShea Nesbit, author of The Wives of Los Alamos, a tale from the top-secret town where scientists developed nuclear weapons; Kristen Millares Young, author of Subduction, about an anthropologist and her collision with the Makah people; and Shena McAuliffe, author of the short story collection We are a Teeming Wilderness, which includes a microorganism character (!). Also on the panel will be Natalie Green, director of the Science and Lit Award at the National Book Foundation.

We’ll talk about inspirations, research, and how fiction shapes perception of the bright and dark sides of scientific breakthroughs.

If you’re attending AWP, please join us! See the other events I’d like to check out. (I can’t actually attend them all.)

What Will Replace the Guidebook?

A moment of frustration in Aden, Yemen, in 1992. Photo by Randa Kayyali Privett.

Remember guidebooks? They used to be the only information source we had when traveling to new destinations, without resorting to an actual, expensive human guide.

Guidebooks survived for a long time into the internet age – I still bought them until the mid-teens. The forces that killed them off include crowd-sourced digital review platforms like Tripadvisor, mobile map apps, and many thousands of online sources paid for by ads or affiliate links. The pandemic delivered the final blow. It was already hard enough for a print product to stay up to date, and the sheer number of places that closed during Covid-19 – and the new ones that soon opened – made anything published before 2020 obsolete.

Unfortunately, nothing has come to fill the role of the print guidebook. Sure, they had flaws, mainly a limited selection of recommendations. This could funnel all travelers to the same few hotels and restaurants. In ambitiously titled tomes covering whole continents, much had to be skipped over. Plus, there was nowhere to cross-check when a guidebook was wrong.

But guidebooks’ limited nature was also their allure. In the days before they were updated by committee, sometimes the author’s personality came through in funny or unique ways. It didn’t take long to skim through one or two. They made excellent jumping-off points, holding your hand for a week or so, after which – it seems to me now – you were expected to stumble off into your own unscripted adventure. If you needed further information, you had to gather it from locals or other travelers.

Perplexity in Croatia, 2000

Now that we have the internet, I could spend weeks looking at AirBnB listings, review platforms, plane fares, travel blogs, and publications I know.

And that’s the problem. It’s a firehose of information, practically forcing me to pick through it out of necessity, FOMO, and a sense of responsibility. I should be the kind of person who does their research, right?

When I tried speeding things up using Microsoft’s Copilot, which incorporates ChatGPT, the results were mixed. I asked it to “Suggest an itinerary for a one-week trip to the Oaxaca coast, including snorkeling, art, and great food.”

It gave me a general outline that helped me hone in on what towns to visit, but broke down on the details. For instance, it proposed a museum that’s an eight-hour drive from the coast and indefinitely closed. For the moment, AI as a travel research tool suffers from the Wikipedia problem: It’s often accurate, but it’s hard to know which parts aren’t.

More generally, AI as a search tool is only as good as a slightly out-of-date internet. (The latest ChatGPT training models only go up to April 2023.) Copilot provides footnoted sources for its answers, which is great. But on the Oaxaca question, its sources were four travel blogs I’d never heard of. Those blogs might be run by savvy, well-informed people, or they might not. In the end, I found travel research via AI chat to be, at best, only a marginally faster version of the long-standing search engines we know and love-hate.

That leaves everyone in a quandary. Where is our smart, curated, edited, one-stop-shop source of info on new destinations? Anybody figured out some good hacks? I’m listening and can share them in a future newsletter.

Five Faves: Ways to End a Nonfiction Story

In addition to my own essays and reporting, I’ve ghostwritten or edited thousands of opinion articles for clients, which has given me a pretty keen sense of how to end a story. Many writers find endings challenging – after all the blood, sweat, and tears they’ve already put in, the prospect of coming up with a brilliant conclusion on deadline looms as too much. So they resort to the “fall off a cliff” method, where the piece kinda stops mid-thought.

But ideally, whether it’s a literary essay, a news story, or an op-ed, you should tie it up with a bow. Here’s a cheat sheet of five ways to do that.

Reiterate your thesis. Difficulty level: 1. What was the general point of your story, which you most likely summarized somewhere up near the top? Repeat this, but in different words.

Quote a source. Difficulty level: 2. Scan your notes for something a source said that crystallizes the theme of the piece.

Call back to the beginning. Difficulty level: 3. Maybe you opened with a simile about cars. Or sports. Or cooking. Then you subtly used related language throughout the piece. At the end, come back to it.

Tell an anecdote. Difficulty level: 4. Relate a situation in which your main character or another source found themselves. The information can be new, but the anecdote should capture and symbolize the general theme of the whole piece.

Reframe your point in a way that follows logically from everything that’s come before, but casts the subject in a new light. Difficulty level: 5. Save your most thought-provoking, unsettling, or emotion-arousing sentence for the end.

And that’s our cue. Until next time,

Elisabeth

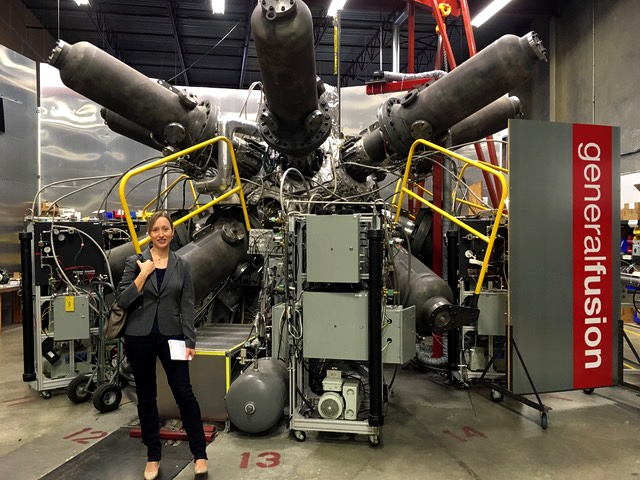

Me with a test reactor at General Fusion a few years back.

Let’s Talk

Write to me at eavesdrop AT elisabetheaves.com. I read every email, and I’ll try to answer every question.

Happy trails,

Elisabeth

Bad Directions

Subscribe to Bad Directions, Elisabeth’s free newsletter about books, writing, and travel.